Getting established; security, speed and space

An introduction

Damon:

Do you ever struggle to answer when someone asks, “So, what do you do?”

I always feel I have about 20 seconds to respond politely, but never managed to explain my role accurately. For the past five years serving in the Medair Global Emergency Response Team (G-ERT), I’ve always failed. So, before my memories fade, I’m determined to share what responding to humanitarian emergencies actually looks like. And who better to join me than my dear colleague, Becks, who’s been shoulder-to-shoulder with me through countless interventions.

Becks:

Such a great question! People always expect a simple answer, but the work is complex and often misunderstood. Hopefully, by putting our experience into words, this document will help readers understand what really happens under the umbrella of an “emergency response”. It’s not as glamorous as people think.

Damon:

Before we get started, I feel our readers should know who you are. You started with Tearfund in the mid-2000’s, moved to Medair around 2008 working in water and sanitation (WASH) in South Sudan, and already had a reputation for being solution-oriented when I joined in 2010. Later you worked with Bristol Water, then ZOA and Medair in Yemen, before joining the G-ERT in 2021 where we first met in Addis. One thing people need to know about you is your unstoppable work ethic – almost as fast as your walking pace. Future colleagues: don’t try to keep up!

Becks:

You’ve been doing your research, Damon - you’ve got it all nailed, some would call that stalking. My time in South Sudan with Medair was a brilliant time of learning and working hard. I’ve also felt it is an immense privilege to work for Medair and do the things we get to do in incredible countries working with such wonderful people - and get paid for it. I’d say we balanced each other well in G-ERT. You taught me to think outside the box, and I have often found myself wondering, “What would Damon do in this situation?” to encourage me to think a bigger and take more risks.

Damon:

I agree with that. A sort of Wallace and Gromit type relationship captures us perfectly. Let’s launch into our first topic of discussion: ‘Security’. Can you kick us off?

Security

Becks:

Medair has a reputation for putting the security of our staff at the forefront of what we do. I know my parents appreciated knowing this. In G-ERT, we were always travelling to new places, often by plane, helicopter, boat, or car. Before we could go anywhere, we had to complete a Rapid Security Assessment (RSA), reviewed by our country lead and security advisor. At times it felt frustrating – we just wanted to get moving – but the process was invaluable. However, in reality, I learnt that in the end although an RSA as a document needed to be signed off, it was the process that I went through in writing the document which was crucial: asking questions, finding out information about permissions, geography and roads, outlining the actors, risks, triggers and agreed check-ins, and a whole load more. Like so much in life, it is the journey we go through, not necessarily the result. How did you view security in the field, Damon?

Damon:

Countless phone calls! I think the security permissions were particularly complex within the G-ERT because of the new geographies and dynamics. Context awareness comes from conversations: with community leaders, other NGOs, the UN focal points, taxi drivers returning from the target region, locals expressing their opinions on social media, friends of friends, distant connections, and of course the deep resource of secondary data harvesting online.

In November 2022. I was asked to set up programmes in eastern Ukraine. The conversations began from my desktop in Normandie, France. A few hours into the quest, I received a forwarded email from info@medair.org. It had originated from a primary health care administrator in a remote community located about 20km from the eastern frontline. About five minutes later we were exchanging messages, and about one week later, we met face-to-face in Kharkiv city. Good connections can come from just about anywhere – which makes me think this role is well suited to extraverts like us, Becks. Can you share some reflections from the Chad setup?

Becks:

When Akou and I went to Chad in December 2023, we visited more than ten towns, travelling either by road or air. Each trip required a new RSA. I remember being in Abéché, staying with another INGO, working late with no electricity and unreliable internet. I managed to send the RSA to James, but then the connection died. No Teams, no WhatsApp – nothing. I was anxious because we needed permission to fly to Adré the next day. There was nothing to do but sleep and pray the internet would come back in time for James to review it, and that he wouldn’t have too many questions I couldn’t answer. Thankfully, the connection returned in the morning, I made the edits, and we got approval. Good communication – or the lack of it – can be one of the biggest stresses, for us in the field and for GSO when they can’t reach us.

Speed

Damon:

In G-ERT we have a target of 24/3/7 – respond within 24 hours, finish assessments in three days, and launch an intervention in seven. To an outsider that might sound slow or fast; in my experience, when you’re starting in a completely new country, it’s incredibly ambitious. We managed it in Ukraine in 2022 and after the Türkiye earthquakes in 2023, but it took the whole organisation shifting into ‘emergency mode’.

Funding, and understanding the different types of funds, is a big part of this. For example, restricted funds are committed for specific interventions, geographies or attached to conditions. Unrestricted funding can be used flexibly to enable responders to jump hurdles and run through walls. Both types of funding are critical for our work, but when we are fighting the clock and every second matters, unrestricted funding is certainly preferable. Becks, I wonder what key points you would share about speed in emergency response.

Becks:

In a G-ERT deployment, speed really is everything. People need help fast, and we do everything possible to get it to them. The 24/3/7 target is incredibly ambitious though. Most of the countries we deploy to have major hurdles – security concerns, government approvals, patchy communications, logistical bottlenecks – all of which can slow assessments and implementation. Do we work as hard as we can to push through those challenges? Absolutely. And, as Damon said, funding plays a pivotal role in making life-saving programmes possible. Just as important is making sure Medair is working in the right place, going where others aren’t, and coordinating with governments, the UN, and other INGOs. A G-ERT response has a lot of moving parts.

Damon:

One of the fastest deployments I remember was after the Türkiye earthquakes in 2023. We landed in Istanbul to news that cities of over 100,000 people had been destroyed in the south-east. It was winter, with sub-zero nights and snow in the hills. The needs were clear, and supplies were available thanks to Türkiye’s strong supply chain. We decided to rent two multi-purpose vans – part distribution point, part warehouse, part accommodation. After driving through the night, we reached the shattered city of Hatay (Antakya) and began distributing blankets and hygiene items the same day. I can still smell the rubble, dust, and smoke – so thick it blocked out the sun. It was an apocalyptic scene: people digging through debris, searching for family and friends.

Space

Becks:

Humanitarian space – or spaces – must be protected at all costs. It’s about more than humanitarians being allowed to work; it’s about ensuring conflict-affected people can access what they need safely and with dignity. G-ERT often negotiates for this space. In Syria, for example, after the 2023 earthquake, I needed a visa, a travel permit for Aleppo, and then approval for Medair to work in specific IDP sites. Frustratingly, that process is never quick.

Ukraine was very different. If the Government was kept informed, Medair staff could travel and work freely. Sudan and Chad, however, were (and are) another story. In Sudan, the Government requires permission for everything – travel, assessments, staff recruitment, office set-up, even basic programme activities. Yemen is similar. That makes responses slow and inefficient. In Chad, registration alone can take up to six months. Without it, we could only work through local partners – helpful, but never at the scale required.

Anything else, Damon?

Damon:

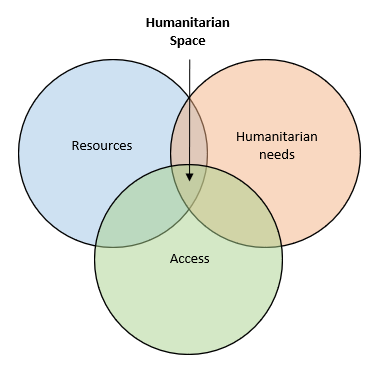

There aren’t many others with your diverse experience of negotiating principled access, Becks. Alongside the critical component of humanitarian space (see Venn diagram provided), our teams also need somewhere to work, rest, and move around. Most people experience war through poverty and displacement, which means warehouses, offices, and accommodation are in high demand but short supply. For the first few weeks of an emergency response, we’ve often slept in vans, tents, airports, and warehouses. In the opening week of our Ukraine response, with more than 160,000 people evacuating to Poland each day, four of us were crammed into one small room. Securing a safe space to rest and work may seem low-priority for altruistic emergency responders, but it’s essential for the team to avoid burnout and keep operations sustainable. Still, humanitarian space is far more interesting than just offices and accommodation – so Becks, perhaps you can share some of your reflections on Ukraine.

Becks:

Ukraine is a very good example of strong humanitarian space granted by the Government. Ukraine is welcoming to INGOs, and there is a high level of trust in their work. Ethiopia in 2021 was a very different context. Tensions in the north were high due to new conflict and there was growing distrust of the international organizations responding. As a result, Medair could not achieve registration which limited our travel permissions. Trying to start new programming became painfully slow. Medair had to work with another INGO with registration to deliver much-needed activities in a neighbouring region that was also affected by the conflict. We succeeded in responding, but it required an enormous amount of persistence and coordination.

Wrapping up

Damon:

And there you have it – the whirlwind world of humanitarian emergency response, where every day is a new adventure and every challenge is met with a mix of grit, determination, and a dash of humour.

From navigating complex security protocols to making friends with taxi drivers and surviving sketchy internet connections, Becks and I have shared some unusual experiences. We’ve laughed, we’ve cried, and we’ve probably eaten more rice and beans than we’d like to admit. But through it all, we’ve learnt that the heart of our work isn’t just about the tasks we complete, but the incredible people we meet and the lives we touch along the way.

Speed is of the essence in our line of work. Our 24/3/7 target – responding within 24 hours, completing assessments in three days, and starting interventions within seven – might seem ambitious, but it’s what we strive for. Whether in Ukraine or Türkiye, we’ve shown that with enough organisational effort, we can pivot into ‘emergency mode’ and make it happen. And let’s not forget the crucial role of funding – unrestricted funds are our best friends when every second counts.

Humanitarian space is another critical aspect. Whether negotiating access in Syria or navigating government permissions in Sudan and Chad, ensuring we can reach those in need is paramount. Sometimes it means sleeping in vans or tents, but that’s all part of the job.

So next time someone asks, “What do you do?” we’ll smile and say: “Oh, you know, saving the world one latrine at a time.” And if they want to know more, they can always read this article. Cheers to the unsung heroes of emergency response – may your internet be stable, your flights approved, and your sense of humour never waver!

Now, where did I put that cup of coffee?

%20(1).webp)

%20(2).webp)

.webp)